With a processing unit in the far south of Brazil, Bionatur has been producing and selling seeds of more than 30 varieties nationwide for 28 years.

“To Hold Up the Sky” is a series of reports that investigates and maps productive initiatives and ways of life of indigenous peoples, quilombolas and other traditional and peasants communities. In our investigations, we explain how these peoples’ contribution to the environment is part of something broader and that these ways of life are not systemic alternatives, but systemic solutions, which need to be central to the actions of government and society to reverse climate collapse.

With hats and boots, Claudinei Anschau and Carla Schmidt guide the Joio reporters through the 29-hectare plot on a March afternoon, pointing in different directions: “This is pumpkin. That’s cucumber. Over there, sunflower and melon. In this section, we’re letting lanceta, cornichão, flor roxa, and chirca grow for the bees.” They take turns speaking, finishing each other’s sentences.

“That area is still lying fallow; we’ll plant it in the winter of next year. This field is where the cows come to graze. In this section, we’ll sow carrots in May and, around June or July, onions,” they add.

For ten years, the couple has been managing an agroecological farm in the settlement of Hulha Negra, in the far south of Rio Grande do Sul. they can’t even explain how they manage to remember exactly what needs to be done in each section of the plot. “At the beginning, we even made a map,” says Carla, “but things change, it also depends on the weather,” Claudinei adds.

At the end of autumn, they will sow carrots and onions on 1.5 hectares. But not to harvest what grows underground. They will wait for the plants to produce seeds.

Os Schmidt Anschau são uma das 120 famílias que fornecem sementes para a Bionatur, a primeira empresa latinoamericana de sementes agroecológicas. É gerida pela Cooperativa Agroecológica Nacional Terra e Vida (Conaterra), do Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST), e completou 28 anos em janeiro. A unidade de beneficiamento fica em Candiota, a 70 quilômetros de Bagé, no Rio Grande do Sul.

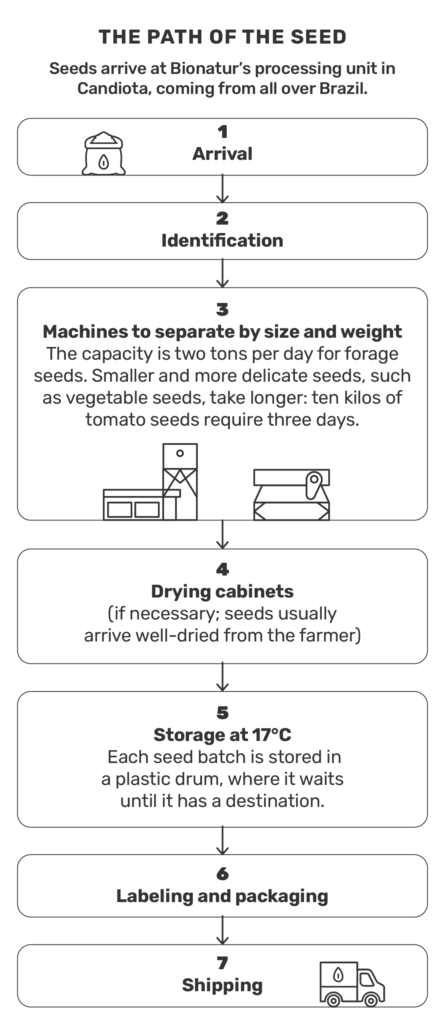

The Schmidt Anschau family is one of 120 families that supply seeds to Bionatur, the first Latin American agroecological seed company. It is managed by the Cooperativa Agroecológica Nacional Terra e Vida (National Agroecological Cooperative Terra e Vida) (Conaterra), of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Landless Workers’ Movement) (MST), and celebrated 28 years in January. The processing unit is located in Candiota, Rio Grande do Sul.

The number of supplying families varies: it started with 12 and reached as many as 350, spread across ten states. With the tightening of public policies under the governments of Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro, the number dropped. Currently, production is about four tons per year, and the seeds come from MST settlers and camped MST families in six states: Rio Grande do Sul, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Bahia, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará. Distribution however, is nationwide.

Bionatur’s journey has taken a non-linear path. Over nearly three decades, the cooperative has changed, experimented, and reorganized in multiple ways. It is now in a sort of off-season phase, ready to start bearing new fruit again. “We are aligning our portfolio with commercial considerations, because we cannot sustain ourselves by producing seeds adapted to only one location,” explains Alcemar Inhaia, president of Conaterra. Bionatur aims to produce eight tons of seeds annually by 2027.

In order to achieve that, a second plant is being planned in Bahia, aiming to decentralize processing and handle production from the Northeast, Central-West, and North states.

A seed produced in Rio Grande do Sul can be sent anywhere in Brazil, but depending on the species, it may not adapt well to a different climate.

One example is Coentro Verdão, a variety planted by MST settlers both in Bahia and in Rio Grande do Sul. These seeds will be sold in nearby biomes, because that is where the plant will grow best. But this does not apply to every seed. “Once we took a lettuce from the South to the Northeast. Its flowering cycle is five months, but in that heat, it flowered in just 20 days, and the plant had barely developed,” Inhaia recalls.

The seed is worth more

The cooperative specializes in seeds of vegetables, which are more delicate and often smaller than those of legumes and fruits. A lettuce seed, for example, is so tiny and light that it can be mistaken for a speck of dust. By the time the plant develops a flower stalk, the leaves of the vegetable have already turned bitter and withered.

This extended cycle requires maintaining the plant’s health over a prolonged period. The price paid to the farmer reflects this, with a higher per-kilo value for the seeds. “A kilo of coriander seeds is bought for R$8 by multinational seed companies. We pay R$18,” points out Daniel da Silva, director of Bionatur.

The harvesting process involves certain particularities, since ripening does not occur uniformly. For instance, by the time carrot and onion seeds are ready for collection, the roots and underground bulbs have already passed the point of being suitable for consumption. The carrots become fibrous, and the onions begin to deteriorate.

These processes do not always interest farmers. The inclination for meticulous work appears intrinsic to agroecology, yet seed production was described as a mission by several farmers. “A lettuce plant can be sold for consumption in 30 or 40 days. For seeds, it takes five months,” Inhaia compares.

Tomato and lettuce without royalties

Bionatur maintains 29 varietals (selected varieties with well-defined characteristics) of public domain, such as onion, carrot, kale, lettuce, tomato, pumpkin, radish, and eggplant. It also preserves more than 40 heirloom species, including vegetables, grains, and forage crops, which are actively shared with networks in other states and donated to interested parties from both rural and urban areas.

glossary

Cultivar

A variety developed through genetic improvement and registered with the National System for the Protection of Cultivars (SNPC), established by the 1997 law. The term is used commercially.

Germplasm

Reproductive genetic material, which can be a seed, a plant cutting, or a bulb, for example.

Varietal

A selected variety with well-defined characteristics. The term is also used as a synonym for cultivar.

Heirloom variety

Selected over generations of farmers, it is adapted to the location where it was “domesticated.”

Bionatur is first and foremost a seed bank rather than a company. Its primary role of supplying settlers with their own genetic material remains at the core of its mission. “Formality guarantees that we can protect the varieties,” notes Silva, director of Bionatur. The cooperative has taken a further step by adapting to the system to challenge the status quo.

The length of time before a seed enters the public domain varies by species, typically 15 to 18 years after its registration with the Ministério da Agricultura e Pecuária (Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock) (MAPA). These varieties are registered as developed by a breeder (a professional working in genetic improvement) or a research institute. After this period, it is no longer necessary to pay royalties to propagate the seed for sale.

Bionatur’s distinctiveness does not lie in the varieties in its portfolio, but in the management: farmers receive guidance from the technical team to produce in an agroecological manner while simultaneously maintaining multiple crops. In addition, all seed production fields are organically certified.

Bionatur keeps around 30 tomato seed varieties, the majority heirloom. One of them was “formalized” in 2017: the Bio Feliciana tomato, selected and cultivated by farmer Lourdes Feliciana da Silva for over 30 years. Feliciana is a settler in the municipality of Piratini, 160 kilometers from Bagé.

To register a seed, it is necessary to select over several cycles those that exhibit the same characteristics. “It took about five years of research and adaptation, because this tomato had high variability. We needed to select plants with traits that ensure it would not be prone to disease, that the cycle would be long, and that it would yield across Brazil. And it really produces a lot of tomatoes,” Inhaia explains.

For now, the Bio Feliciana tomato is the only seed as Bionatur’s intellectual property. All other varieties were developed by the Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation) (Embrapa) or by the Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), and Bionatur holds the license to market them. However, when registering the Bio Feliciana tomato, Bionatur chose to forgo royalties. In other words, anyone can propagate Bio Feliciana seeds for sale without paying a fee to the cooperative.

In recent years, Bionatur has been working to register its second proprietary variety, the Bio Rainha lettuce, following the same approach.

From Default to Nationalization

Claudinei and Carla are children of MST-settled farmers. The first families arrived in the region in the late 1980s, the majority coming from the northern part of the state. Today, 1,700 families live in 57 settlements in the cities of Candiota, Hulha Negra, and Pinheiro Machado, the region with the highest number of settlers in the state.

In fact, the permanence of farmers throughout the far-south region was challenging for decades. The Bagé region had been strong in wheat production until the 1970s. “At the time, it was corn and wheat, the basics. But they were small-scale farmers. They also grew other crops, like potatoes, cassava, and pumpkins for subsistence,” recalls Luís Flávio Soares Abreu, a native farmer of the region, known as Kiki.

Land concentration and the modernization of agriculture in the state caused a rural exodus that, in the 1970s alone, displaced more than 1.2 million people from rural areas to urban centers. Kiki’s mother and siblings were among them. “My father and I stayed. We were the only two left in the countryside,” he says. He is 61 years old and has a daughter who is a teacher.

The farmers arrived without understanding the soil and the climate, what to plant, or how to work the land. The soil is hard, the winters are dry, and at the time tools were nonexistent. Plowing and turning the fields relied entirely on manual labor. They gradually learned which species to plant and when to plant them.

Local farmers, like Kiki’s family, worked for large seed or monoculture companies. For generations, they cultivated the land using animal manure, green manure, fallow periods, and mixed planting of different varieties. At the time they did not know it, but their method of production was agroecological. “That’s when those of us who were here joined the landless movement. Agroecology was already being discussed, and we were unsure about it. Then we began to understand what it was and that we were doing it too. Not out of awareness, but out of necessity,” recalls Kiki.

The first employment opportunities came through seed-producing companies that were already established in the Pampa, a biome in Rio Grande do Sul.

The location is no coincidence: the longer summer days and distinct seasons are ideal for the growth cycle of vegetables. This allows them to complete their full development in the soil, from sprouting and growing to flowering, fruiting, and producing seeds.

Without access roads or electricity, and still living in black tarpaulin tents, the settlers began producing seeds for the region’s major companies. Initially, they cultivated onions, carrots, and parsley. This arrangement continued for about three years, until the companies claimed germination issues and ceased payments. The seeds were not returned to the farmers, despite the fact that the seeds could have been used for food production.

After the default, 12 families came together to begin independent seed production. In 1997, they established a seed division within the dairy cooperative that existed at the time in the Conquista da Fronteira Settlement in Hulha Negra. From the start, the goal was to produce vegetable seeds agroecologically. The following year, they harvested their first crop under the name Bionatur.

The production was shared among family farmers, operating as a seed bank, including forage crops, grains, flowers, and ornamental plants.

In the 2000s, Bionatur relocated to the Centro de Educação Popular e Pesquisa em Agroecologia (Center for Popular Education and Research in Agroecology) (Ceppa) in the Roça Nova Settlement in Candiota, a neighboring town of Hulha Negra. The location improved the logistics for receiving and sending seeds.

In 2005, a new cooperative was established to manage Bionatur: Conaterra. Discussions within the MST determined that the strategy for nationalizing production was to increase the number of producing families. The decision also served as a response to the recently enacted Biosafety Law, which removed the requirement for health and environmental assessments in the approval of a genetically modified organism. Seeds were central to the debate on food sovereignty and farmer autonomy, and their agroecological production was established as a priority for the entire movement, from Oiapoque to Chuí.

The settlements operated locally, managing their own seed production and exchanging seeds among themselves. However, it soon became clear that without central coordination, nationalizing production would not succeed.

“There has to be someone guiding the process, because it’s not just a matter of taking the seed and multiplying it. Traditionally, farmers know corn, beans, and rice. You plant them anywhere and they will multiply. But how do you multiply lettuce, arugula, or escarole?” Inhaia asks. The choice of seeds was also strategic: diversity was necessary, and it was important to offer a mix that could compete with the commercial production of multinational companies.

Formal System and Genetic Erosion

Plant reproduction is generous by nature: the seed harvest from one hectare of radishes fills a 20-liter container in the Gaúcho Pampa, and this volume can go on to sow hundreds of other fields.

Farmers need two things: land and seeds. The former was turned into private property centuries ago, but seeds, until quite recently, were shared resources.

The first law regulating the sale of seeds in Brazil was Law 4.727, passed in 1965 with the aim of setting standards. It was in this same decade that the Green Revolution transformed agricultural production through its technological package of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and agricultural machinery.

Seeds played a central role in this process. The same industries that developed the technological package began working on selecting varieties with higher productivity. These traits, along with shorter life cycles, remain the traits preferred commercially today.

Whereas farmers once kept their own “libraries” of seeds already adapted to the climate and soil conditions of their regions, the pressure to increase production, the legal requirement for standardization, and the emergence of cultivars from seed companies led many to stop saving, exchanging, or selling their own seeds. They began using seeds from multinational seed companies instead, whether they were selected varieties or hybrids, the latter resulting from a cross between two parent lines.

In the first case scenario, farmers can still save seeds and replant them in subsequent years. However, as seasons pass, new genetic combinations cause the plants to lose the uniformity of their original characteristics. This process, called segregation, is natural. In the second case, the hybrid vigor that gives the plant higher productivity decreases with each cycle, and new seeds must be bought to sustain the same productivity.

Two decades after the Green Revolution began, researchers and plant breeders had already begun noticing a sharp decline in genetic variability. Irajá Antunes, an agronomist specializing in plant breeding at Embrapa Clima Temperado, notes that in the 1980s an international movement emerged to collect and preserve heirloom genetic materials.

“With the advent of what I call synthetic agriculture, modern agriculture, the process of genetic erosion was greatly accelerated,” he says. “And the more diverse an ecosystem is, the more resilient it will be. In the face of the climate change we are experiencing, we increasingly need genetic diversity in the fields.”

With one foot in agroecological farming and the other in the formal commercial seed system, Bionatur now faces three interconnected challenges. The first is ensuring specialized technical assistance for producers across Brazil. This, in turn, increases seed production and stock. Finally, higher sales volumes boost income in rural areas. Kiki, the eldest of the group, views this optimistically: “The cooperative is young. There is much to build, and it will only get better.”