MST aims to scale up agroecology with the use of affordable machinery tailored for small rural properties

“To Hold Up the Sky” is a series of reports that investigates and maps productive initiatives and ways of life of indigenous peoples, quilombolas and other traditional and peasants communities. In our investigations, we explain how these peoples’ contribution to the environment is part of something broader and that these ways of life are not systemic alternatives, but systemic solutions, which need to be central to the actions of government and society to reverse climate collapse.

At 7 a.m. on a Tuesday in May 2025, an unusual noise filled one of the rice fields in the Diamante Negro Jutaí settlement. Piercing and monotonous, it stood out from everything that had been heard around there before. Even at that early hour, the novelty was already attracting a small crowd. Five men and a child were closely watching the source of that noise. It came from China, or rather, from two small machines manufactured in that country. They had crossed half the globe to get there, the city of Igarapé do Meio, 220 kilometers from São Luís, in Maranhão, northeastern Brazil. The mini harvesters were a big deal for a very simple reason: they did in a few days the work that took almost a month to be done before.

“You do 24 days’ worth of work in just two or three. If it [the machine] doesn’t break down, we can do it in one day,” figured enthusiastically Railson Sousa Lima, the owner of the plantation where the harvesters were going back and forth.

The two machines are of different models, and were manufactured by the Chinese company Shineray, a manufacturing enterprise that owns a motorcycle factory in the Suape Industrial Complex in Pernambuco, Brazil. The larger one, a 4lz-1.0lc model, has 15 horsepower and is approximately the size of a golf cart. The smaller one has 10 horsepower and vaguely resembles one of those vehicles used by shopping mall security guards. With an average price of 4,000 dollars each, the small harvesters are much cheaper than the closest alternative sold in Brazil, which costs 550,000 reais.

The little machines not only harvest but also speed up the rice cleaning process. The grain grows in clusters. Harvesters suck up these clusters, separating each tiny grain and throwing the cereal into sacks. “The rice comes out ‘beaten,’ just ready for drying,” stated Railson.

That moment marked the completion of approximately one hundred days of work that had started on January 13, with the land preparation for planting. The Sousa Lima family’s rice was the first to be ready for harvest in the Diamante Negro Jutaí settlement. And the settlement, in turn, had been one of those chosen by the Landless Workers Movement (MST) to test the viability of an ambitious plan: to make agroecology accessible to the masses through the mechanization of family farming. On top of that, to also contribute to the reindustrialization of Brazil.

Railson was happy with the rice harvest. “Our rice is in high demand because it’s organic rice. And of good quality,” he said.

Photos: Ingrid Barros / O Joio e O Trigo

A striking difference

Founded in January 1984, MST emerged with the agenda of land reform in a country whose agrarian policy predominantly benefited the model of large estates focused on monoculture for export. But starting in the 2010s, the movement added a word to its slogan. It began to speak of popular land reform. The occupations, which symbolized the movement so strongly in the 1990s, continue to take place, but now with the goal of producing agroecological food in Brazil.

The land reform settlements produce food, but this is not always done on a scale large enough to supply the domestic market. Gaining traction and strength became a central goal. “I mean, moving beyond pilot projects, moving beyond very localized experiences, and truly nationalizing agroecology in our settlements, in peasant agriculture in general,” explains Luiz Zarref, who, in addition to being a member of the MST, is the coordinator for Latin America of the International Association for Popular Cooperation (Associação Internacional para a Cooperação Popular), also known as Baobab.

Founded in 2019 by movements such as the MST, Baobab focuses on international cooperation in the fields of science and technology. To this end, it promotes exchanges between popular organizations and government institutions, research institutes, technology developers, funders, and entrepreneurs from the so-called “Global South.” It has offices in Accra, the capital of Ghana, in São Paulo, and in Beijing, where Zarref currently resides.

The address in China is no coincidence. To gain scale, both MST and other organizations that make up Baobab view mechanization as the answer they need. But the machines for family farming need to be small and affordable. Meeting these two conditions was not easy. Zarref explains that the movement searched in countries like Italy, Germany, Japan, and South Korea. The search had to be outside Brazil because the suitable models for this purpose are not manufactured here.

“In fact, we recently discovered that China would be the country with the most suitable technologies for the Brazilian peasant reality,” says Zarref. “In China, there are 240 million rural establishments, most of which are no larger than half a hectare.”

The size matters a lot: in such small areas, about the size of half a football field, large machines don’t make sense. The Chinese industry, heavily directed by the state, provided an answer to this reality by creating suitable machinery. According to the coordinator of Baobab, the country has more than 8,000 agricultural machinery factories. “It is a country that carried out land reform effectively and industrialized its rural areas, based on a government political agenda.”

Meanwhile, in Brazil, the same year that Baobab was founded, the governors of the Northeast decided to counter the disastrous actions of Jair Bolsonaro government during the COVID-19 pandemic by creating the Consórcio Nordeste ( Northeast Consortium). Later on, the organization, which brings together all the states of the region, would turn its attention to other areas besides health, such as family farming.

Being aware of Consórcio Nordeste’s interest in the topic, Baobab connected them with Chinese researchers and agricultural machinery manufacturers. “It had a big impact,” recalls Zarref. The distance between China and Brazil, especially between China and northeastern Brazil, proved to be striking.

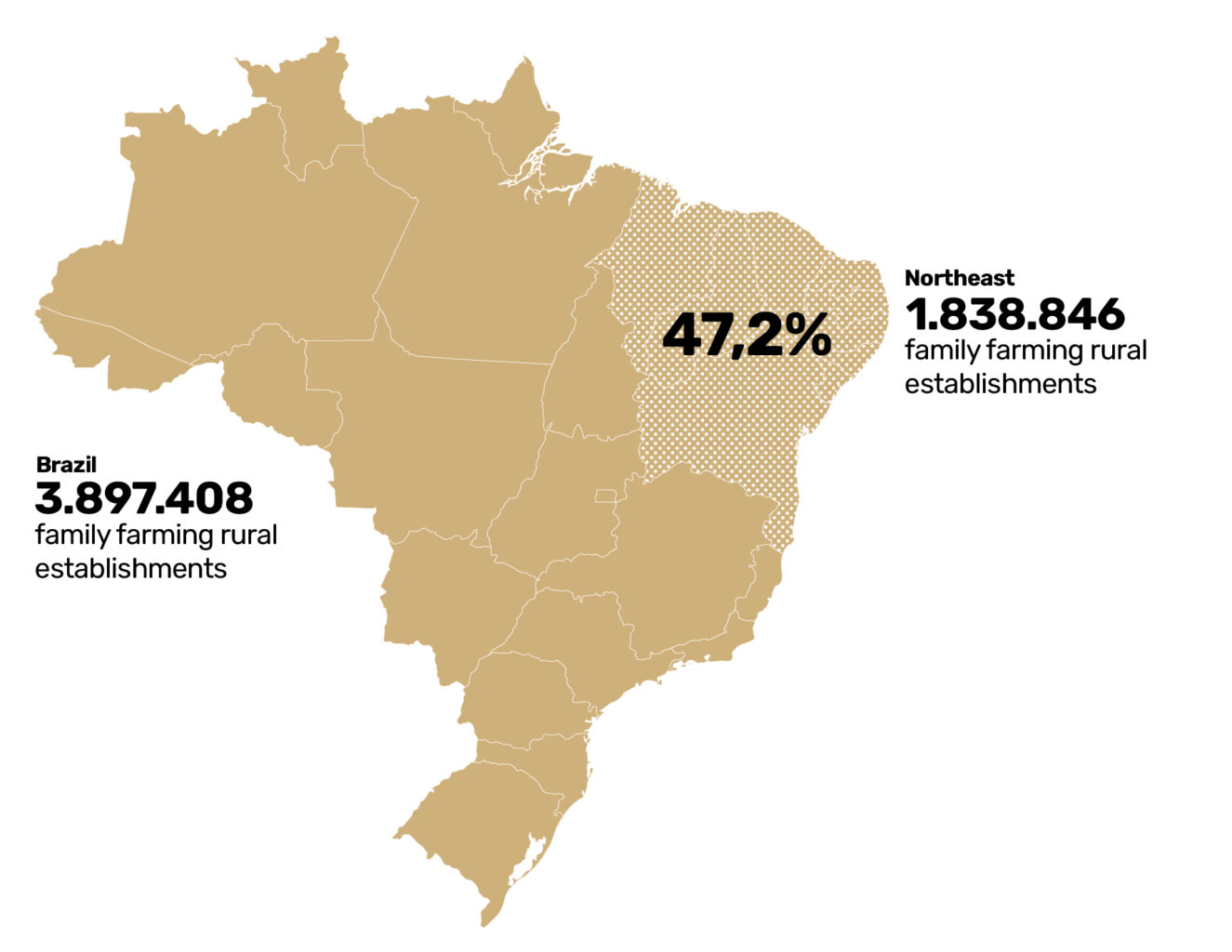

According to the latest Agricultural Census conducted in 2017 by IBGE, there are 3.8 million family farming establishments in the country. Half of them are located in the Northeast.

The census does not provide an average for mechanization in this category of property, but it does present data on some types of machinery. If we take the most common one – the tractor – mechanization reaches 12% of family farming establishments. In the Northeast, the rate is 1.3%. “In China, [the average mechanization] reaches 72%. In some production chains, it reaches 83%,” compares Zarref.

The desire to shift the game paid off. In September 2022, a memorandum of understanding was signed among Baobab, Consórcio Nordeste, the Belt and Road Institute of China Agricultural University, and the Association of Agricultural Machinery Manufacturers of that country.

After a survey of which production chains could be boosted with machinery manufactured in China (vegetables, corn, beans, and rice), 31 machines arrived in Brazil in February 2024 with a defined destination and purpose: they would be tested in MST settlements in the states of Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, and Maranhão.

Massive participation

On May 4, 2025, a beautiful sunny Sunday, Maria de Jesus woke up early, made breakfast for her children, and headed to the headquarters of the Mixed Cooperative of the Land Reform Areas of the Itapecuru Valley (Cooperativa Mista das Áreas de Reforma Agrária do Vale do Itapecuru, Coopevi). Once there, the hours would fly by, racing against the clock, since the National Land Reform Fair was just around the corner; the Fair is an event organized by MST in São Paulo that serves as a showcase for food production in settlements from all over the country. Dijé, as Maria de Jesus is known, joined the task force to prepare the products that would be sent to the capital, São Paulo. Tapioca, flour, syrup, jam, lemon, pumpkin… But, most importantly, rice.

The first harvest with the Chinese machines was of that rice, and it took place a year earlier, right there at the Cristina Alves settlement, located in Itapecuru-Mirim, a municipality 119 kilometers from São Luís. Dijé was the only woman from the Northeast settlements to operate a Chinese machine, the largest of the Shineray harvesters.

“I took it to see if I could [drive it]. Then, when I managed to, I went around many times, cutting rice. And it was a really great moment, you know? We felt very happy about it,” she recalled.

For Dijé, just like for Railson, the shock came from the time saved not only during the harvest but also in the cleaning process, since the grain comes out without the husk. “It’s ready for us to put in the sun and take to the mill. And I used to spend the whole day cutting six sacks, with husk, with everything. [With the machine] in four, five minutes, we have a full fifty-kilogram sack. What a difference! …then I got excited, because I always participated in the rice field, but I had never harvested my own.”

“It’s more interesting for popular land reform and for agroecology, that people’s participation also be massive. Not just production on a larger scale, but participation on a larger scale as well.”

Elias Araújo, coordinator of MST production sector in the Amazon region.

The goal of Coopevi is to attract more people to rice planting. The cooperative is about to make a leap with the installation of a mill financed by Secretaria de Abastecimento, Cooperativismo e Soberania Alimentar do Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário in partnership with Fundação Banco do Brasil. The facility will have the capacity to process 8,000 kilograms of rice per day. For the mill to operate efficiently, the area planted each harvest needs to increase from the current 20 hectares to 500 hectares. However, the goal is not to expand production solely within the settlement.

“This would be monoculture. It goes against what we want to discuss in terms of agroecology,” explained Elias Araújo, a long-time member of MST in Maranhão who has lived in the settlement since its creation in 2007 and now coordinates the movement’s production sector across the entire Amazon region.

According to him, the plan is to gradually expand the planted area within Cristina Alves, from 20 hectares per harvest to 150 hectares and mobilize people from outside to plant the remaining 350 hectares. “It’s more interesting for popular land reform and for agroecology, that people’s participation also be massive. Not just production on a larger scale, but participation on a larger scale as well.”

Photo: Ingrid Barros / O Joio e O Trigo

This is where the Chinese machines align with the plans that the cooperative has been developing for some time. They serve as a bait. “To harvest one hectare of rice today, it takes about 20 days, at least. With this little machine from China, you can harvest it in one day. It’s a revolution,” said Elias. “We want to work around the settlement, get other families involved. There are several settlements here, and many quilombola communities…”

In Maranhão DNA

Rice is essential to the culture of Maranhão. The state has the highest per-capita consumption in Brazil by far. Annual consumption is 49 kilos of rice per inhabitant, according to the IBGE. For comparison, in Bahia and São Paulo, the number drops to 15 kilos.

This culture has already undergone several upheavals and even faced prohibition. At the beginning of the colonization of the Americas, Maranhão was a contested territory by the Spaniards, the French, and the Portuguese. The latter brought the rice consumed in the Azores Archipelago to the region — a red variety that achieved enormous success – until the Crown prohibited its production in 1772.

At that time, Portugal was experiencing a supply crisis. But the metropolis was interested only in white rice. As a result, the people of Maranhão were forbidden to plant the red rice they enjoyed so much, while Brazilians perhaps lost the chance to add more variety to their plates.

Today, red rice has even made a comeback but as a niche product for middle and upper-class consumers seeking a healthy lifestyle. Currently, 70% of the rice consumed in the country is white polished rice.

Rice is also linked to the history of Maranhão’s territorial occupation and to its injustices. It is a crop associated with clearing land: it is what is planted after cutting down the forest. “You remove the timber and make the first field. And the first field that comes is the rice field,” stated Elias.

“Plus, in the wake of this shifting cultivation, there were the cattle ranchers. And following all of this came what we here have called the legalization of the land. The more enlightened people like merchants and outsiders were documenting the areas. And the peasants were being expelled,” pushed further and further into the Amazon.

Maranhão once reached the position of Brazil’s second largest rice producer. The last time the state achieved this ranking was in 2006, according to the Agricultural Census.

Today, Rio Grande do Sul accounts for 70% of Brazilian production, with 7 million tons in 2023. It is followed by Santa Catarina, Tocantins, and Mato Grosso do Sul. Maranhão ranks fifth.

Maranhão in Brazil’s rice production

1970

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 1.383.516 tons

2nd Goiás – 893.374 tons

3rd Maranhão – 650.852 tons

1975

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 1.876.215 tons

2nd Goiás – 1.100.296 tons

3rd Maranhão – 894.165 tons

1980

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 2.249.425 tons

2nd Goiás – 1.337.975 tons

3rd Maranhão – 1.026.084 tons

1985

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 3.537.302 tons

2nd Maranhão – 779.322 tons

3rd Goiás – 771.280 tons

1995

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 4.645.427 tons

2nd Mato Grosso – 588.731 tons

3rd Maranhão – 561.255 tons

2006

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 5.637.239 tons

2nd Maranhão – 1.092.705 tons

3rd Santa Catarina – 846.378 tons

2017

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 8.408.352 tons

2nd Santa Catarina – 921.634 tons

3rd Tocantins – 513.581 tons

4th Mato Grosso – 430.727 tons

5th Maranhão – 135.538 tons

2023

1st Rio Grande do Sul – 7.142.801 tons

2nd Santa Catarina – 1.176.285 tons

3rd Tocantins – 604.375 tons

4th Mato Grosso – 324.706 tons

5th Maranhão – 184.752 tons

(Source: 1970–2017, Agricultural Census. For 2023, Municipal Agricultural Survey / IBGE)

In Elias’s assessment as an agronomist, Maranhão lost ground because it did not modernize. “The crop shifted to regions where it found response, where productive forces advanced.” Even within the state, he says, rice production now comes more from agribusiness than from settlements or traditional territories. “In the south of Maranhão, where the machinery is, where it is possible to plant and harvest.”

MST itself takes pride in the rice produced in Rio Grande do Sul. According to the Instituto Riograndense do Arroz (the Rio Grande do Sul Rice Institute, Irga), the movement is the largest producer of organic rice in Brazil. And, given the scale of production, it is likely the largest one in Latin America. According to MST, in the last harvest (24/25), 2,850 hectares of agroecological rice were sown in Rio Grande do Sul settlements by 290 families—an average of 9.8 hectares per family. The idea is to replicate this scenario in Maranhão.

“That peasant who used to plant the rice field and harvest it manually still exists, but only to meet a consumption need. When that family improves financially and can buy rice from elsewhere, they will no longer stay in rice cultivation,” says Elias, for whom the way to keep people working in Maranhão’s countryside necessarily involves mechanizing rice production.

Major changes

“When the forest was still standing, we were able to make the traditional fields. But it was collective land. You had large areas that you could cut, clear, burn, and plant. You would rotate, letting the area rest, and it would regenerate over time. Today, the settlement has already been divided; everyone has their own plot,” explained Lucas Machado, a farmer from the Diamante Negro Jutaí settlement. There, the lots are 30 hectares, with ten hectares designated as legal reserve. “Our alternative was to mechanize.”

He put into practice on his family’s plot everything he learned in the course. He had a goal in mind. “Coming here to show that we, within the settlement, can produce just as well as a large landowner. That the settlement also has this potential.” Knowing the settlement’s aptitude for rice production, he wanted to deepen his study of mechanized cultivation.

In the rice production chain, one machine drives another. This is because in order to produce at scale and sell, certain market requirements must be met. The grain needs to be long and slender. Broken rice is not valued, hence the need for a grader.

The dryer, for example, is a machine that is of no use to someone practicing stump cultivation, because the rice is harvested in clusters. And since these clusters protect against moisture, the rice can be stored in a simple granary — which could even be the doorway of the house.

It is quite new. Mechanization in the settlements is an ongoing process, with experiments that sometimes fail.

This is what happened with the BRS 502 seed in the case of Cristina Alves settlement. “The variety gave very good yields in Diamante Negro Jutaí,” said Elias Araújo. “But here it showed a far lower germination rate, around 20%. So it impacted the crop, making it unviable.”

Despite the fact the Chinese machinery was available, Cristina Alves had no rice to harvest and had to make do with stocks from previous harvests.

Another devastating factor also played a role: the climate emergency. The rains, which were supposed to start in January in the region, were delayed by a month. “And we will have to learn to live with this; this factor in agriculture will now be permanent,” remarked Elias.

Elias shows the area he had planted with rice in January, which didn’t take. By May, his plot was already planted with beans. In detail, a single bean. Photos: Ingrid Barros / O Joio e O Trigo

Next steps

In different territories, circumstances vary greatly, but in the end, the Maranhão settlements selected to test the Chinese machinery pursue the same political guidelines: producing agroecological food at scale.

In May 2025, a second partnership agreement with China was signed, this time involving the Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário e Agricultura Familiar (Ministry of Agrarian and Family Agriculture Development) (MDA). The new phase includes testing 50 more machines in MST settlements, as well as at the Universidade de Brasília (UnB). There, the Centro Brasil-China de Pesquisa, Desenvolvimento e Promoção de Tecnologia e Mecanização para Agricultura Familiar (Brazil-China Center for Research, Development, and Promotion of Technology and Mechanization for Family Agriculture) was created, which will also focus on the study of bioinputs and digitalization technologies. “It’s not just a matter of mechanization,” explains Luiz Zarref.

In parallel, MST is trying to set up factories to produce these small, low-cost machines in Brazil. Originally, the movement thought it would be possible to attract Chinese capital directly, since some of the companies that manufacture the small machines in China are established in the country, but producing other items — such as motorcycles, as is the case with Shineray itself.

But without a specific policy guaranteeing a market for the companies, it was not possible. “Not having a more consistent mechanization policy for family agriculture ends up discouraging companies from taking the initiative to come to Brazil—which is a distant market — and setting up an industrial plant to produce machines for this type of agriculture. Because, once there’s no policy for it, these machines will likely remain unsold,” says Zarref.

Now, the plans have shifted slightly. They involve a triangulation between public authorities, national capital, and MST cooperatives. “So, at this moment, we are in discussions with Chinese companies, trying to find ways to create either joint ventures or technological partnerships,” says the Baobab coordinator and MST member.

It would work roughly like this: the Chinese company transfers the technology, and the MST cooperative, supported by public and private investments, manufactures the machines.

“Through a public-private and popular partnership. The movement’s cooperative joins in and has a stake, but it’s important that there be public funding and that an investor is available. So, as long as these three elements don’t converge, there will be no industry in Brazil,” asserts Elias Araújo.

In Maricá, in Rio de Janeiro, something along these lines is already underway—also the result of coordination with Baobab and the MST. In July 2025, the city hall signed a memorandum with the Chinese company Sinomach Digital Technology and the Brazilian company OZ.Earth. The plan is to set up factories for agricultural machinery for family farming and to develop digital platforms for equipment management.

In Elias’s view, the city in Rio de Janeiro state is an example that changing the reality of mechanization in Brazil is not a distant ideal. “The machinery industry in Maricá is just getting started. Without appropriate machines, without suitable industries, you don’t have agroecology at the scale we are demanding.”