The American manufacturer received tips on entering the Brazilian market from executives in the Brazilian tobacco industry and estimated electronic cigarettes would be released in the country by 2024, according to internal company documents

U.S. electronic cigarette maker Juul explored launching “low-cost vapes” in Brazil, considering distribution in bars and small neighborhood stores where anti-smoking rules are “generally not enforced”, internal company documents reveal. These records, reviewed by Joio, were obtained from the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents (TTID) archive at the University of California.

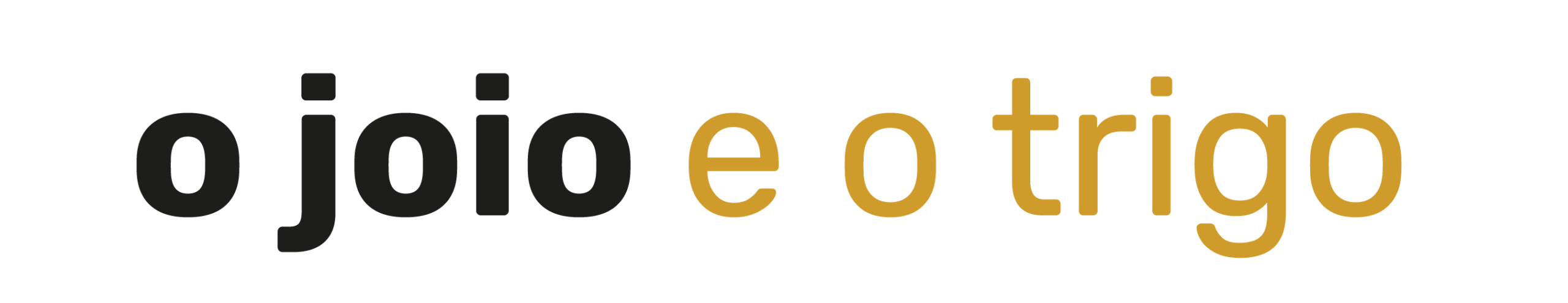

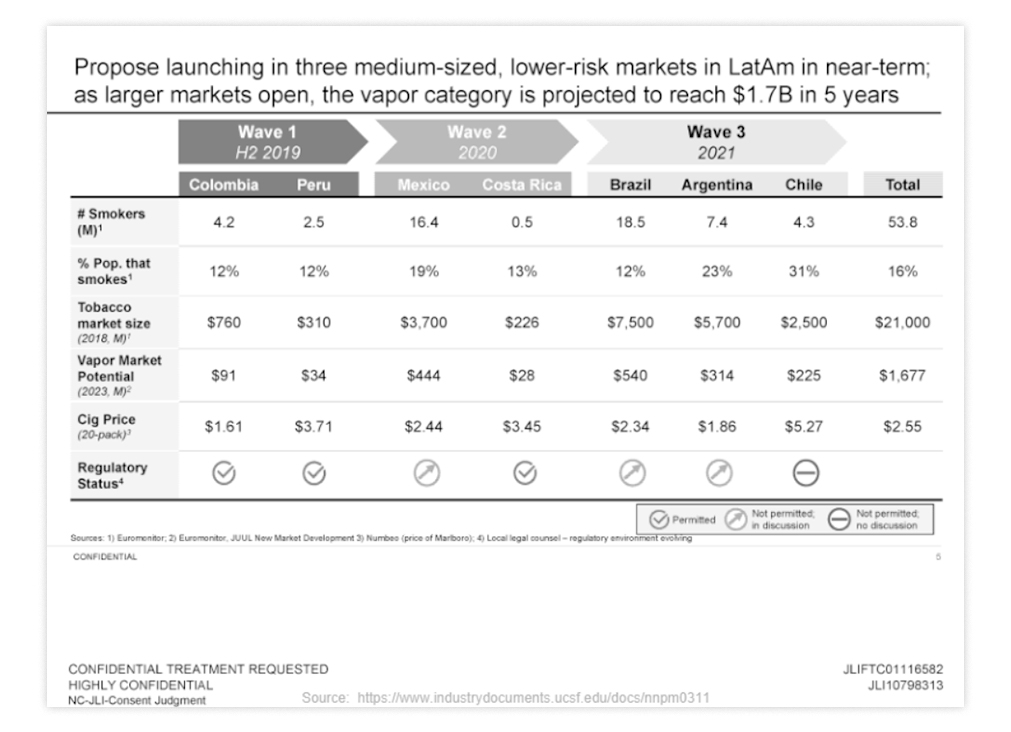

Brazil was a priority in Juul’s global growth plans, according to the reports. The company identified a potential market of more than 18 million people and projected sales of up to $540 million in Brazil—nearly one-third of its total revenue forecast for Latin America. To reach these consumers, Juul considered launching an inexpensive vape that could be equivalente to a whole pack of cigarettes and priced at about $6.12 (35 Brazilian reals)—and refills at $1.40 (8 reals), according to internal analysis.

However, Juul’s ambitions in Brazil collapsed after the company faced dozens of lawsuits in the United States, alleging it marketed to teenagers and contributed to rising teen vaping and related lung illnesses. Earlier this year, nearly 4 million internal emails and documents were turned over to TTID through settlements, which required Juul to pay at least $462 million in damages.

The full repository from the University of California can be accessed here. Joio reviewed about 40 documents from the collection, focusing on Juul’s plans for Brazilian consumers.

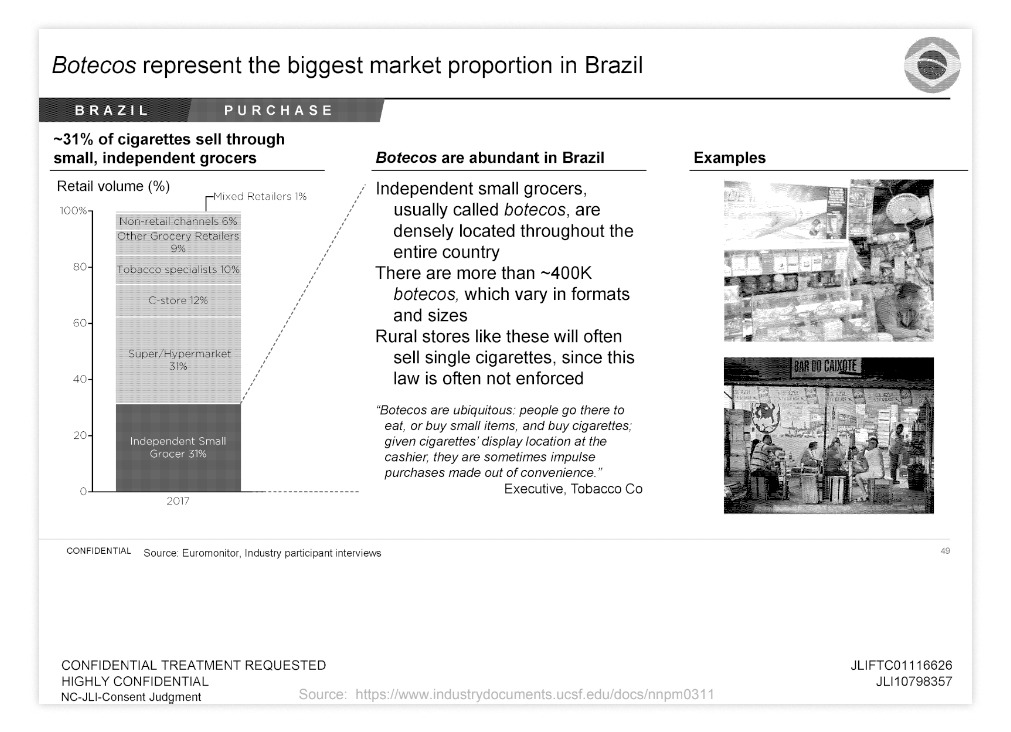

One document, titled “A deep dive into Brazil,” notes that small businesses—bars and groceries—would be central to vape distribution in Brazil, since few comply with legal requirements like the ban on selling loose cigarettes or rules about displaying tobacco products inside stores, away from candy and snacks. The report suggests such restrictions make buying cigarettes more “onerous” in supermarkets and large retail chains.

“Botecos are everywhere; people visit to eat, purchase small items—and buy cigarettes,” explained a Brazilian tobacco industry executive, whose identity was withheld in the study. “Cigarettes tend to be displayed at the register, which encourages impulse buys.” These small outlets and bars generate 31% of Brazil’s cigarette sales, according to Juul’s analysis.

Since electronic smoking devices (ESDs) have been banned by the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) in Brazil since 2009, Juul’s research included conversations with former Philip Morris and BAT (formerly Souza Cruz) executives about future regulation in Brazil. Industry veterans described ANVISA as unwilling to open discussions, but predicted a five-year window for legalization—by 2024. Juul appeared even more optimistic, anticipating legalization in 2021 and projecting $214 million in annual revenue in Brazil by 2023.

“Brazil usually follows Canada on regulation; over there, vape shops are legal—and regulators are looking to tighten rules. Brazil is likely four to five years behind,” commented a former BAT executive—the company behind brands like Dunhill and Lucky Strike—in a 2019 Juul report.

Today, tobacco manufacturers are among the main supporters of a bill introduced by Senator Soraya Thronicke, of the Podemos party in Mato Grosso do Sul, to legalize electronic cigarettes in Brazil. Meanwhile, Canada has implemented new product restrictions amid an escalating youth vaping crisis, spending millions on prevention campaigns. In 2022, Vuse, BAT’s U.S. vape brand, was the country’s second-most popular e-cigarette among high schoolers, behind only the Chinese brand Puff Bar.

Juul told Joio the company does “not sell its products in Brazil or in any market that prohibits the sale of electronic cigarettes.” At that time, Juul was pursuing international expansion, buoyed by a 35% equity purchase by Altria—the parent company of Philip Morris, maker of Marlboro and L&M. Philip Morris’s Brazil operations said they have “no commercial relationship with Juul” when contacted for this story.

Influencers first, cheap vapes later

These market studies were part of a confidential strategy called “Project Ernest,” which sought to probe consumer habits in key markets in anticipation of global vape launches. Priority focus countries included Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, and Brazil. The planning was commissioned to consulting giant Bain, involving its São Paulo office.

Asked for comment by Joio, Bain said: “does not comment on work carried out for its clients, which takes place under confidentiality policies, and clarifies that its work is restricted to the planning and execution of strategic projects”.

Project Ernest’s goal was to brand ESDs as a safer alternative to traditional smoking, targeting current cigarette users while avoiding the “vape” label, which the company felt might alienate more conservative, predominantly male audiences. “A vaper community already exists, and smokers may feel unable to relate,” Juul’s then-product director Nihir Shah wrote in a December 18, 2018 email—one of the project’s early exchanges.

Positioning electronic cigarettes as “harm reduction” tools to help people stop smoking has underpinned manufacturers’ campaigns to win legalization, even without solid public health data to support it. In practice, countries such as Canada, the United States, and the UK have all seen significant upticks in smoking linked to vaping, though those governments argue electronic cigarettes are a safer option for smokers.

“When legalization comes, we see an explosion in usage—not among those who want to quit, but among young people who never previously used any product,” said nurse Stella Bialous, a University of California professor who oversees the TTID-hosted Juul archive. “It’s people who never consumed nicotine now starting to vape,” she said.

Emails show that, until a low-cost model was available, Shah believed “existing [Juul] products can reach the upper and middle classes, drawing in influencers and early adopters to generate momentum and social acceptance” in developing markets.

“In such countries, we require a robust social media approach,” Juul’s director argued, believing affordable models would only succeed once there was “popular confidence in the product”. “Our interviews indicate that YouTube reviews and Facebook posts are seen as primary sources of cigarette and vaping information,” Shah said.

In countries like Brazil, lower price points are essential for market penetration, as Juul’s research found most smokers fall into lower-income, less formally educated demographics.

The most recent TTID-covered documentation about Project Ernest, dated April 2019, shows Juul’s cost models for countries including Brazil foresaw devices priced between $8.24 and $12.38 (56 to 84 reals at prevailing exchange rates).

Today, many electronic cigarettes smuggled over the Paraguay-Brazil border cost less: a disposable Ignite vape touted for 15,000 puffs—currently among the most coveted—sells for $7.50 (40 reals).

‘Brazil – a good example of what we want to avoid’ INTERTÍTULO

Even before Project Ernest, Juul was eyeing Brazil. Company records indicate intense demand for its devices and a significant opportunity in the Brazilian market. In September 2017, Brazil topped the list for illicit online Juul sales, becoming the largest market for unauthorized distribution, with most sales routed through e-commerce giant Mercado Livre.

That August, Juul tallied 6,100 violations on Mercado Livre’s Brazilian site—far exceeding the 1,400 cases on eBay in the United States, which ranked second. Notably, three of Juul’s top five most prolific online resellers were based in Brazil.

Yet this ongoing problem with illicit sellers didn’t stop Juul from holding discussions with smugglers seeking Brazilian distribution. In January 2017, VapoKings, a retailer in the state of Santa Catarina, reached out by email about Pax herbal vaporizers—a Juul brand—despite noting the devices were “banned by the Health Department.”

Juul knew the devices were prohibited in Brazil. A year earlier, in 2016, the company’s attempt to register the Pax brand with ANVISA was rebuffed, though ANVISA declined to confirm the registration attempt to Joio. Nonetheless, Juul took a receptive tone with VapoKings, telling the company its “compliance team” felt “importation shouldn’t pose a problem for Brazil.”

Ultimately, the deal fell through as VapoKings refused to become an official distributor, offering only to purchase small retail volumes without a formal agreement.

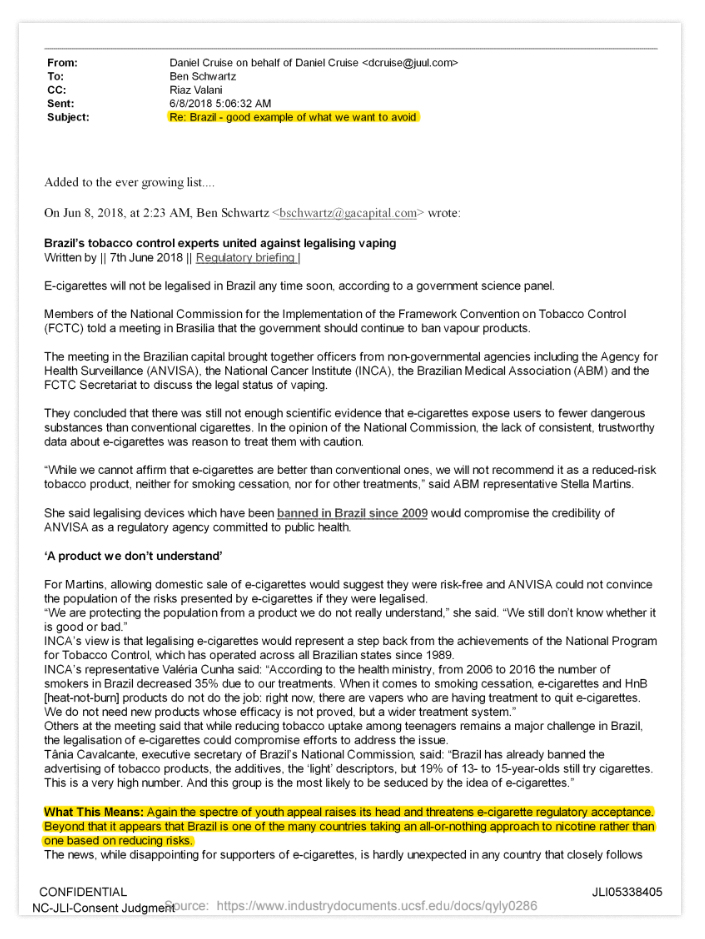

Juul’s interest in Brazil, however, continued. In August 2018, executive Ben Schwartz circulated an internal message, “Brazil – good example of what we want to avoid,” addressed to colleagues Riaz Valani and Daniel Cruise, both Juul investors.

Schwartz referenced a “regulatory briefing” on a June meeting between Brazilian ANVISA, the National Cancer Institute, and the Brazilian Medical Association, where legalizing electronic cigarettes was robustly debated and ultimately dismissed by experts. The prevailing consensus cited a lack of trustworthy scientific evidence for vaping’s claimed “harm reduction” or smoking-cessation value—two pillars of Juul’s global marketing.

“Brazil is among several countries staking out an ‘all or nothing’ approach to nicotine, rather than risk reduction-based policies,” noted Juul’s internal briefing shared with senior leadership. “While the news is discouraging for electronic cigarette advocates, it’s par for the course in a country that closely follows the guidelines of the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, ratified in 2005,” the note concluded.

“There’s harm reduction logic for oral medication or for nicotine replacement therapy. But with vaping, though, you see people taking one thousand, five thousand puffs a day,” said psychiatrist Carolina Costa, vice president of Brazil’s Association for the Study of Alcohol and Other Drugs. “There are people sleeping with a vape under their pillow, waking up afraid because they inhaled while sleeping and don’t remember doing so. In other words, these products are highly addictive and do not save your lungs.”