How the corporation and Pepsi receive at least US$ 2 billion a year in credits for taxes that have never been paid, and how a senator and former ministers help them, despite a warning of illegal enrichment

Brazil’s major soft drinks manufacturers receive between US$ 0.05 and US$ 0.10 in subsidies for each can of drink consumed. For the two-litre bottles, the amount refunded to the companies is between US$ 0.15 and US$ 0.20. Between the amount not paid into the public coffers and the amount leaving them, each Brazilian pays more than US$ 10 a year in incentives granted to Coca-Cola and Ambev in particular.

Their competitors, the Department of Federal Revenue, the body responsible for taxation in the country, and health organizations, want to dismantle an operation that involves receiving credits for taxes that have never been paid. Many incentives are given to companies that produce soft drink concentrates (syrups) in the Manaus Free Trade Zone, which is a free-trade area established in the Brazilian Amazon.

According to the (conservative) calculations carried out by O joio e o trigo, they amount to at least US$ 2 billion a year in an operation that makes Brazil one of the most profitable countries in the world for Coca-Cola. The Department of Federal Revenue confirms that there is a “distortion”. Nor do all of the incentives appear to be sufficient for the companies in the sector: tax invoices that we have obtained indicate over-invoicing.

The situation results in an unusual occurrence: an economic sector that provides a loss in government revenue. According to the Department of Federal Revenue, the production of soft drinks in 2014 led to a negative tax on manufactured products (IPI) of 4%.

According to the Brazilian Constitution, taxes between one industrialization stage and another are not cumulative, “with what is owed for each transaction offset by the amount received in previous transactions”. In other words, if the industrialist buys concentrate for R$ 100 at a rate of 20%, he is entitled to R$ 20 in credits.

In the case of the Free Trade Zone, the IPI is zero, but the buyers demand a credit higher as if they payed the tax imposed on the product manufactured in other regions, currently 20%. The result is that the Brazilian tax on soft drinks, already low, ends up even lower.

Coca-Cola’s main activity is actually manufacturing concentrate. Recofarma, a subsidiary of the multinational in Manaus, sells the intermediary product to bottlers who dilute it in water and gas, package it and take care of distributing it.

It was in the 1990s that the leading companies in the sector started to transfer production of concentrates to the Amazon. Not satisfied with the ‘standard’ incentives, they started to receive credits for tax payments that they never made. The Department of Federal Revenue initiated legal proceedings to contest the activity, but was only partially successful.

We obtained tax invoices that show that a kilo of concentrate from Ambev and Coca-Cola from the Free Trade Zone cost up to R$ 450 (US$ 140). The lowest price we found was R$ 169 (US$ 52).

The syrup produced by Recofarma (Coca-Cola) in Manaus is supplied to all the bottlers in Brazil, as well as Argentina, Colombia, Paraguay, Venezuela, Uruguay and Bolivia. Therefore, we have a reliable basis for comparison. A kilo of the same product sent to the international market costs US$ 22, around R$ 70. In other words, at best, the domestic market price is double that amount and, at worst, more than six times the amount.

There is an even stranger case: the infusion known as mate. A kilo of mate in natura costs from R$ 10 to 15. Production is totally concentrated in the south of the country, and the Matte Leão factory, which Coca-Cola bought in the previous decade, is in the state of Paraná, also in the south. An invoice we obtained shows that a kilo of mate concentrate cost R$ 351 (US$ 110) after leaving Manaus upon its return to the region. This is a product that theoretically cost 8.000 kilometres to be turned into tea.

The leading concentrate companies account for less than 1% of labour employed directly in the Free Trade Zone of Manaus, but they collect 12-13% of revenue. The chemical sector, dominated by the production of syrups, is by far that which has progressed the most in terms of value since the 1990s. Whereas the number of workers increased tenfold between 1988 and 2013, revenue in dollars increased 200-fold.

According to the most recent public survey, Recofarma has 175 employees, while Arosuco, owned by Ambev, has 142.

Looking at public data, we saw that the chemical sector is always second in terms of state tax refunds, despite not always being second when it comes to tax payments. Last year, for example, R$ 140 million were paid and R$ 1.167 billion received. The motorcycle sector, with more employees and a higher turnover, paid more (R$ 155 million), and received less credit (R$ 365 million).

Illicit enrichment

As far back as 1994, the Office of the Public Prosecutor of the National Treasury warned that the tax credit scheme would result in “illicit enrichment” and “tax evasion”. In response to legal proceedings launched by Coca-Cola, the body asserted that there was no logic to receiving compensation for tax that has never been paid.

The activity in the Free Trade Zone leads to a curious situation: we see a business sector that wants higher taxes because the higher the rate, the more credit it receives. In 1997, the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper announced that the then governor of Ceará, Tasso Jereissati, put pressure on the Ministry of Finance to reverse the decision to abolish the tax for concentrates.

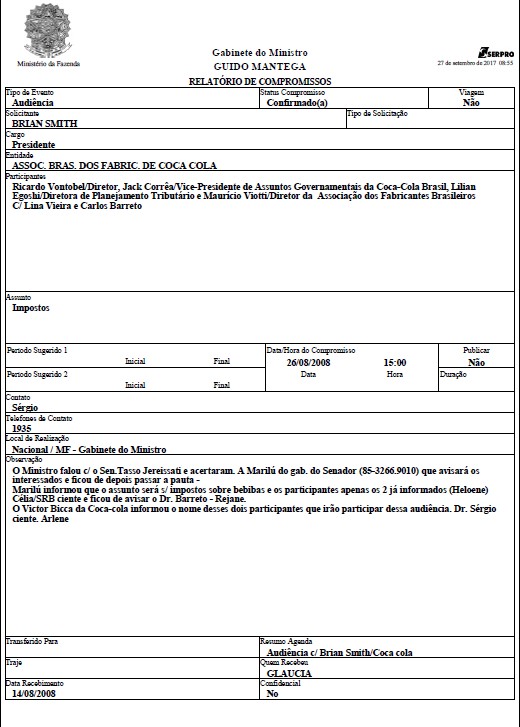

A document we obtained illustrates that the current senator used his public office to obtain business benefits. The second largest bottler of Coca-Cola products in Brazil and owner of declared assets of US$ 120 million, Jereissati brokered a meeting between the president of the multinational in Latin America, Brian Smith, and the then minister of finance, Guido Mantega.

“The minister spoke to Senator Tasso Jereissati and they agreed. Marilú, at the office of the senator, will notify the stakeholders and then circulate the agenda. Marilú announced that the topic would be tax on drinks.”

The meeting took place at 3 p.m. on 26 August 2008, when a bill was going through Congress regarding a tax on non-alcoholic drinks. At that time, the regional producers were successful in changing the tax regime, which benefitted the major players in the sector.

However, three days after enacting Law 11.727, a provisional measure was issued by Mantega’s team which basically reinstated the previous situation.

At the end of that year, the then president Inácio Lula da Silva signed a decree to maintain the favourable situation for the major companies, guaranteeing lower tax for tin and glass packaging, which was not widely used by regional manufacturers. The Department of Federal Revenue was hoping to guarantee a gradual reduction in the disparity and that the problem would be resolved by 2018.

Once again, however, the political arena took precedence over the technical arena. On 30 May 2012, a decree by Guido Mantega indicating the reduction of the gap was published in the official journal of the Government of Brazil. Nevertheless, five days later, the government republished the decree, claiming that there had been a mistake. What actually happened was that the tax scale for packaging was changed completely. The government put off until 2015 a correction that should have been made in 2013.

On 25 September of the same year, Mantega met with entrepreneurs from the drinks sector at the request of the then president of Ambev, João Castro Neves. The meeting was requested the previous day and did not feature in the official agenda. The same situation arose on a number of other occasions.

In the second half of 2013, the minister signed a new decree further postponing the correction of the distortions. The aim then was to reach 2015 at a level below that expected for 2014.

On 30 April 2014, Mantega brought about a slight readjustment, which was revoked exactly one month later on the grounds that the increase would put pressure on prices during the World Cup in Brazil.

The case became public because not everybody is winning. The Association of Soft Drinks Manufacturers of Brazil (Afrebras) was created in the previous decade to dispute the tax on the sector, seen as benefitting the major companies. On the other hand, the Brazilian Association of Non-alcoholic Soft Drink and Beverage Industries (ABIR) states that it accounts for 93% of revenue.

“The major corporations say that they are more efficient. No, they are not more efficient. They are more efficient at creating and manipulating Brazilian tax legislation,” accused Fernando Bairros, President of Afrebras.

Abir denies that the operations in the Free Trade Zone benefit only Coca-Cola and Ambev, claiming that any company can avail itself of the generous incentives. However, there are some questions. First, picking up the raw material in Manaus and transporting it to the south or south-east of the country, where most of the factories are located, is costly. Second, since tax credit is paid, whoever buys more asks for more, and is therefore more powerful.

The credits moderately benefit a small-scale producer but, for large-scale producers, they are a billion-dollar incentive. They can be transformed into subsidies to lower prices and destroy the competition, into advertising to increase market share, and into resources to buy space on supermarket shelves and undermine rival companies.

According to Afrebras, there were 892 soft drinks manufacturers in 1960, and 235 in 2015. In 2000, the small companies were producing 2.72 billion litres, as opposed to 1.04 billion 15 years later. During the same period, which coincides with the peak of the credits in the Free Trade Zone in Manaus, the large companies went from 5.78 billion to 13.86 billion.

Supreme friends

The debate could have taken a different course 20 years ago. In 1998, the Coca-Cola case was judged by the Supreme Federal Court (STF), the highest court of law in the country. “There can be no doubt. The Constitution is extremely clear,” says Ilmar Galvão, now 84 years old, the minister who reported the appeal by Coca-Cola. “The court allowed itself to be influenced by Minister Nelson Jobim’s vote. I was defeated. Alone. I was defeated, yet unconvinced, because the court was wrong.”

Jobim had recently arrived from the Ministry of Justice under Fernando Henrique Cardoso, in a contentious move from the Executive to the Judiciary. He took to the court a business vision of the case, disregarding the Constitution. “I know about the existence of a virtual conflict between the Ministry of Finance and the Coca-Cola producers concerning margins. According to information, the syrup producers increased their value in order to obtain greater exemptions.” In other words, the minister acknowledged that there was suspicion about over-invoicing; however, instead of putting an end to the scheme, he called a vote that consolidated it.

Ilmar Galvão still regrets the decision. “Jobim, when he was minister of Justice, was in a mess between Coca-Cola and Guaraná. Coca-Cola put syrup production in the Free Trade Zone. Guaraná is from the Amazon. There was a controversy between the two and Jobim was focusing on that.”

Jobim is currently a member of the advisory board of the Brazilian Fair Trade Practices Institute (ETCO), a think tank supported by Coca-Cola and Ambev, and did not want to comment on the case.

His son, Alexandre Kruel Jobim, has been the president since 2015 of Abir, which is headed by the two multinationals. He claimed recently that the sector suffered from bullying.

“We cannot fail to mention that there is a distortion in the drinks sector regarding extract”, said the General Coordinator of the Department of Federal Revenue, Fernando Mombelli, during a recent public hearing in the Chamber of Deputies. He warned that any increase in tax without correcting the problem would be useless, as it would be offset by tax credits.

After Jobim’s departure, the Supreme Federal Court slightly changed its opinion on the case, but there is no consensus among ministers as to how to deal with the matter, which is also reflected in lower court decisions.

At the end of October, the Department of Federal Revenue took another step towards putting a stop to the loss of revenue, issuing an interpretation according to which the companies have produced a concentrate kit and not the concentrate itself in the Free Trade Zone, which would make it possible to prevent the private sector from receiving compensation.

Coca-Cola and Ambev stated that Abir would issue a position on the case. In turn, the association issued a general comment on the situation and did not justify the difference in value between concentrate sold on the domestic market and concentrate exported.

Jereissati ignored the requests made by O joio e o trigo. Guido Mantega’s secretary stated that the former minister had personal issues and was not in a position to grant interviews.