In the Ribeira Valley, in the state of São Paulo, the Agroecological Network of Women Farmers produces an abundance that escapes the logic of the market

“To Hold Up the Sky” is a series of reports that investigates and maps productive initiatives and ways of life of indigenous peoples, quilombolas and other traditional and peasants communities. In our investigations, we explain how these peoples’ contribution to the environment is part of something broader and that these ways of life are not systemic alternatives, but systemic solutions, which need to be central to the actions of government and society to reverse climate collapse.

Every last Thursday of the month, very early in the morning, a truck begins traveling the winding road between hills that connects the town of Barra do Turvo, in the interior of São Paulo, to the BR 116 highway, which cuts across Brazil from north to south. It collects foods cultivated and produced by about seventy peasant women farmers organized into eleven groups that form the Network for Supporting Agroforestry Women, known as Rama.

As daylight grows, the truck picks up the boxes placed by the roadside by peasants from the rural neighborhoods where Rama participants live. Into the boxes go seedlings, flours, coffee, breads, beans, hearts of palm, brown sugar, lard, banana and cassava chips, savory snacks, sweets, jams, preserves, honey, cheese and ricotta, pasta and cakes, seasoning mixes, fruit pulps, herbal remedies, vegetables, greens and fresh fruits. In all, it amounts to around one ton of hundreds of varieties of vegetables and dozens of artisanal food products.

In February 2025, when we visited Barra do Turvo, one of the products being offered was the subject of conversation across the country due to rising prices: eggs. In this case, free range chicken eggs, sold by the farmers at fifteen reais per dozen, while in São Paulo supermarkets the same dozen reached nineteen reais. Prices within the network are adjusted only once a year, during assemblies of producers and consumer groups, regardless of increases in food costs. This is possible because the organization’s commercial system, which turns ten years old in 2026, is not based on market principles

Its foundations are solidarity economics, feminism, agroecology, food sovereignty, the defense of the territories and ways of life of the peasant women, and the fight against racism and all forms of violence. These principles are also adopted by the network of solidarity consumption groups that purchase food from Rama, called Esparrama — a word that, in Portuguese, describes the movement of spreading out, scattering, which the branches of plants perform as they grow. They are self organized groups in the cities of Registro, Diadema and São Paulo. The operating agreements of the network were collectively developed and protect the women’s autonomy over their production. The adoption of rules different from those practiced in the market makes it possible to set fair prices, both for those who produce and for those who buy.

One of the secrets to Rama’s price stability is that “the peasant women have autonomy in relation to the market connected to the global economy, its fluctuations and the financial market’s speculations,” notes Natália Lobo, a technician from the team of Sempreviva Feminist Organization (SOF), which provides technical assistance to the network.

“It is different from being a producer who needs to buy nitrogen fertilizer to plant, and when there is a war in Ukraine the price of fertilizer skyrockets. Another thing is to have a production system that is quite autonomous in terms of the inputs needed for planting and raising animals, with relations that are far less commodified compared to the rest of conventional agriculture” she explains.

Furthermore, if egg prices rise because corn prices rise, there is always the possibility of buying corn from neighbors, through relationships of care, trust, interdependence and reciprocity that are also cultivated among the women. The same applies to seedlings and seeds, donated or exchanged, and to the knowledge built through their planting experiences in backyard fields, always shared among them. The value of these relationships is not recognized by classical economics.

Commitment to women

“We started Rama to support women’s rights. Because there were many women who suffered, many women without a voice, mistreated by their husbands, many were beaten and had no right to any money, nothing, just depending on the husband, right? That was what came first.” This is how Dona Dolíria Rodrigues de Paula, a resident of the Ribeirão Grande–Terra Seca quilombo, explains the origin of the network in 2015, beginning with a rural technical assistance and extension project by SOF in the Ribeira Valley.

Nilce Pontes, coordinator of the Ribeirão Grande–Terra Seca Quilombo Association, a participant in Rama and in the National Agroecology Articulation, says that the relationship between SOF and the quilombola communities began at the Third National Agroecology Meeting, in 2014. “SOF was already implementing the rural extension program in the region. So Miriam Nobre, also from SOF, came to talk to me.”

At that time, in Barra do Turvo, there was rural technical assistance and extension from the rural workers union and from Cooperafloresta, an agroforestry association. But the women needed something that took into account their condition as… women. After the conversation at the agroecology meeting, SOF went to Barra do Turvo to introduce itself to the quilombola women. Dona Isaíra Maria de Pontes Maciel Pereira, Nilce’s mother and granddaughter of Miguel Pontes Maciel, founder of the Ribeirão Grande quilombo, asked: “This work of yours — is it a service or is it a commitment?” It was a commitment. And it still is today.

In the Ribeira Valley, on the border between the states of São Paulo and Paraná, lies the largest continuous stretch of Atlantic Forest in Brazil, totaling 1.7 million hectares. Many traditional communities live there: quilombolas, Guarani and Kaingang Indigenous peoples and caiçaras. The women who form Rama live in rural communities of Barra do Turvo, a municipality with 6,900 inhabitants. Most have worked in their fields and backyards since childhood, using management techniques learned from mothers, grandmothers, great grandmothers and neighboring peasant women.

The women of Rama have different forms of access to land, or lack of access, depending on how the communities they belong to were formed. In addition to quilombola women, there are small farmers who came from other states and descendants of rural worker families from Barra do Turvo. The quilombola communities have lived in the region for generations and participated in the creation of Cooperafloresta in 1988, bringing with them their traditional knowledge of how to grow food among trees, without needing to clear the cultivation area and replant everything after each harvest. They live within the Atlantic Forest.

In 2005, these communities formed an association to seek self recognition as quilombo descendants and demand legal titles for the lands they inhabit. Within Rama, there are also women who have been organized in the Pastoral da Criança, a Catholic Church affiliated organization, since the 1980s; women mobilized in resistance against the takeover of their lands by conservation units; and family farmers with little or no cultivation area — whose lands were taken over by ranches or sold by elders to large landowners for little or almost nothing, amid land conflicts caused by cycles of monoculture expansion or livestock in the municipality.

In 2015, in partnership with SOF, a process began to bring visibility to the work of women in their homes and backyards and to value their role in the economy of their families and communities.

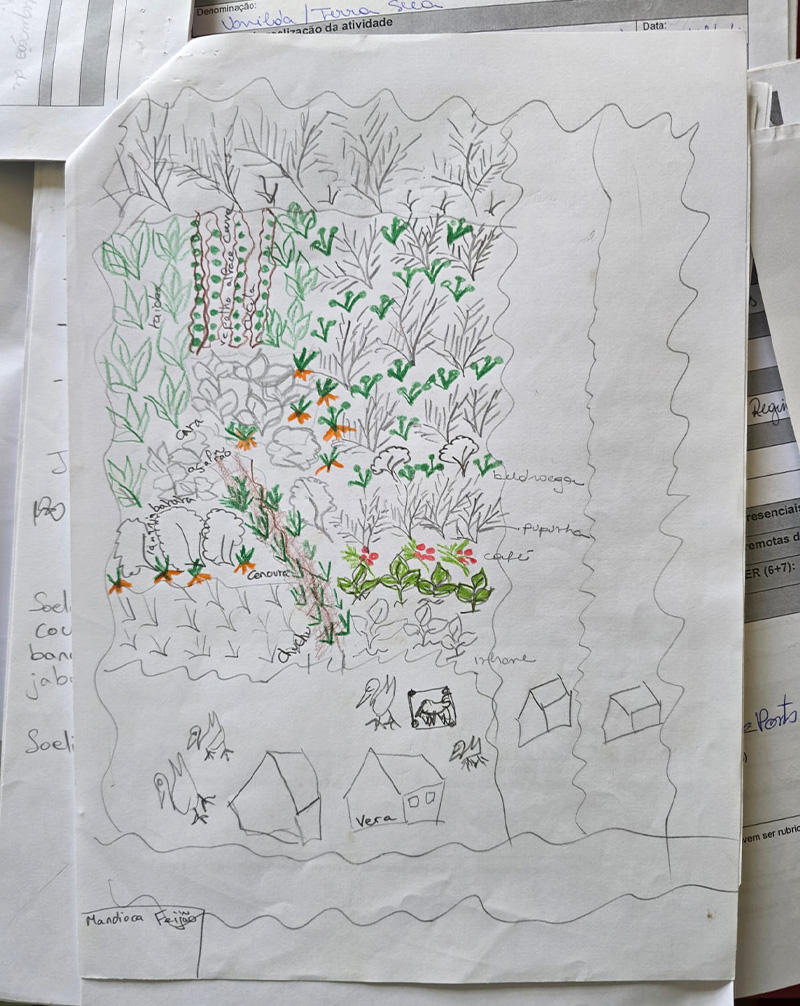

One of these women is Vera Lúcia Lourenço Costa, from the Indaiatuba neighborhood. “I am an agroecological farmer, the daughter of farmers. I participate in movements that mobilize women, such as Rama, I am part of the Community that Supports Agriculture and of the Seed Spiral of Paraná. I live in Barra do Turvo and I have a small plot of land, and I survive from it. Here we have everything we need to live. We plant everything together and mixed, there are many varieties — more than a hundred.”

“We do not have any large scale planting of anything; it is all in small amounts, so that we can consume and sell the surplus. Even so, we lose a lot of produce here, a lot indeed.” There is no effective way to capture, in writing, the abundance of the women’s backyards in Barra do Turvo. What may look like a groceries shopping list is, in fact, a description of the abundance that exists in a place the state of São Paulo considers “poor” when viewed through cold economic indicators. And even this list leaves many things out. The forests. The rivers.

Vera cultivates an area where the Turvo River bends. When there is a flood, the river takes everything. When the water recedes after the flood, everything begins again. There she is, once more cultivating her backyard, without using pesticides or chemical fertilizers — just caring for the soil and using organic matter to maintain its fertility. The year before last, she sowed fourteen different varieties of beans, but lost seven because of the rains. This year she planted seven and lost three. She will rebuild her seed diversity and plant again. Meanwhile, in the green and fertile world that is this river bend, dozens of other plants grow — greens, fruits, hearts of palm, tubers, vegetables. All together and mixed.

Diversity

“Fields, (roças) are areas normally used for specific and temporary production: cassava, corn and beans. In the traditional way of producing, there is rotation of the planted species and also rotation between the places where the fields are established, so the soil can recover its fertility. Backyards, or quintais, are spaces that women cultivate around their homes and manage on a daily basis. They include, in addition to food production, ornamental and medicinal plants, experiments with seedlings and seeds. And also flowers and other beauties that seem to serve no purpose, but bring well being to those who care for them. “The backyard is everything around our house — everything we planted, everything we have, everything we grow,” says Dolíria. “Almost all the women have one. ”

The diversity of Vera’s backyard is not an exception among the peasant and agroforestry women of Rama. “Spaces under the domain of women have greater diversity and greater complexity of management than those managed by men,” wrote, in 2018, Liliam Teles — who is part of the Women’s Working Group of the National Agroecology Articulation and a member of the World March of Women — in her dissertation “Unveiling the invisible economy of agroecological women farmers: the experience of the women of Barra do Turvo, SP”.

This diversity of production is the starting point for Rama’s purchasing system, where the method of commercialization was created to accommodate the farmers’ output. Each month, they report what they will harvest in their gardens and backyards, and the consumer groups place their orders based on that offer. Over almost ten years of commercialization, there has never been a shortage of food or handcrafted processed foods like cheese, jams, cookies, and cakes. On the contrary. “Every time there is a discussion about adjustments, in the assemblies, they say they prefer for more groups to be formed or for existing groups to buy more, instead of raising prices,” notes Natália, from SOF. Because, as Vera explains to us, much production is still lost.

One of the tools used to highlight women’s monetary and non-monetary production was the Agroecological Notebooks (Cadernetas Agroecológicas) project, implemented by the Women’s Working Group of the National Agroecology Network and funded by the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA) in 2016, before the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff. The project was developed in dialogue with women from social movements and technical advisory and rural extension organizations, such as SOF, throughout the country. Women farmers from Barra do Turvo participated.

In the notebook, they recorded their daily harvests for a year, noting the volume and monetary value of the produce that was for their own consumption, for sale, for exchange, or for donation. This work with the notebooks showed that seventy per cent of the value of the food produced by women in the Córrego da Onça neighborhood, and thirty two per cent in the Terra Seca quilombo, went to self-consumption, essential for ensuring the families’ food security.

In the production carried out by men, whether in their own monocultures or on land belonging to others, the harvest happens once a year. In the women’s production, however, an important portion feeds their immediate and extended families throughout the entire year. One of the agreements among the women farmers is this: “Our production is destined first to our own food or to the family we live with, those who live in other cities, children, relatives, comadres. Never take food off the table to sell.”

Food security

People who live in the Ribeirão Grande–Terra Seca quilombo do not buy beans at the supermarket. They plant them. In January, Claresdina Alves dos Santos celebrated the harvest of feijão pardinho, which was enough for all seven of her children to take ten or twenty kilograms home. Beans for almost the entire year, despite the rains that caused part of the production to be lost — and that portion will return to the soil and become fertilizer. Her lychee trees also yielded a lot, and she sold many boxes.

Data from the 2017 Agricultural Census, conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), count as lychee producers in Barra do Turvo only those who have more than fifty trees. Dona Claresdina, who has fewer than fifty, does not appear there. The jackfruit tree in Dona Dolíria’s agroforestry plot, which yields between 150 and 200 kilograms of jackfruit “meat” per year, also does not appear. Nor do Vera’s oranges. Nor the coffee that Nilce Pontes plants, harvests, roasts, drinks every day and serves to visitors, unaffected by market prices. Nor the eggs from Córrego da Onça, which were consumed by the women farmers’ families and also came on the February truck.

None of this appears in the agricultural production accounts of Barra do Turvo because the way IBGE conducts the Census does not consider this diverse production — and in quantities that, when each backyard is considered individually, seem small. By organizing through Rama, the women make this production visible collectively — and then its scale becomes closer to what it represents in the real world.

The Agricultural Census uses the agricultural establishment as its unit of analysis. “We are always fighting for it to be improved so that it can show what happens within this unit: how the work is organized, the inequalities. Whether the person responsible for the establishment is a woman, a man, or whether it is a case of shared responsibility, where there is co management,” says Miriam Nobre, from SOF.

These data show that, throughout Brazil, in establishments where the main purpose is self consumption, 56 percent have a woman as the person responsible. In 39 percent a man is responsible, and in 43 percent there is co management. The Census, however, does not show the economic weight of production for self consumption in establishments where the main purpose is commercialization. “This is what the agroecological notebook reveals,” Miriam points out.

The notebook began to be created and used among women farmers in the Zona da Mata region of Minas Gerais, who wanted to understand how families continued producing coffee despite market prices fluctuations. Through the research, they understood that continuous production for self consumption provided stability for families facing fluctuations in the prices of inputs and of the product itself, as well as variations in harvests due to climate.

“Before the notebooks, the peasants themselves did not have much notion of what they produced, because they had never stopped to record something that is part of their daily lives. “We did not value the things we had. It was like… Wow, we have all this?” says Dona Maria Izaldite Dias, from the Bela Vista neighborhood in Barra do Turvo. In this process, they began to see how much of their food comes from their backyards. “We saw it was important and started planting more. Soon we had enough to eat and also to send to São Paulo, when we were able to make those sales.” The sales are very important, she says, because they give women freedom. “Before, they had to ask their husbands for everything. With the sales, they can go and buy some things with their own little bit of money, right? Have an income, help at home.”

Simone Rosa, Noeli de Lima, Eliene de Lima, and Dilma Rosa de Lima.

Photo: João Ambrósio / O Joio e O Trigo

Another form of invisibility concerns access to public policies. In Córrego da Onça, the women have very little land to cultivate. They live on small lots, where their families were squeezed as monoculture ranches expanded.

Rama includes, in its list of offerings, foods prepared in home kitchens — such as breads, jams and cakes. This is one dimension of solidarity among the women farmers: in this way, even those who do not have land, or have very little, can participate in commercialization. In addition, collectively, the women identify spaces in the community where gardens can be established. Another important initiative was registering the women in the National Registry of Family Farming, the CAF. Only with this document, which recognizes as farmers those who live from planting and raising animals, can they access social security rights and federal, state and local public policies that support family farming.

To obtain the registration, it is necessary to prove a relationship with the land. But the women of Córrego da Onça do not even possess the minimum land area considered “land” under the criteria of the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Farming. Starting in 2016, they began recording their production in the agroecological notebooks and their sales through Rama. With this information in hand, they requested a meeting with the ministry and managed to obtain their CAF registrations, with the condition that they attempt to expand their production and commercialization area.

With the CAF, the women of Córrego da Onça became eligible to receive a grant offered through the Rural Women technical assistance program of the ministry. They nicknamed the grant “yeast” — after all, it helps the production grow. They decided to use it to build chicken coops.

Collective care

Dona Izaldite trained the other women at RAMA to use agroecological notebooks. She saved the money she received for her work and, during the pandemic, organized a fundraiser to supplement the funds and build the Sala do Aconchego Esperança (Hopeful Comfort Room). There, she makes herbal remedies and welcomes women who need support and conversation. She provides a level of care that all RAMA women consider to be of the utmost importance. Whenever one of them feels discouraged, she finds strength in the others. “These groups brought that to us. We need a look, a hug, some affection,” Izaldite says emotionally. “Because we care about each other.”

Collectivity is part of a way of living. Farmers in the Ribeira Valley have always organized mutirões — moments of collective work to help one another cultivate their lands. Rama was the first organization to carry out mutirões composed only of women, as shown in the documentary “Vida em Mutirão”, and the first to include kitchen work in the list of tasks performed — which did not happen in mixed mutirões or those coordinated by men. The women listen to each other more, take better care of one another and are better prepared to respect each woman’s way of doing things, and they do not separate productive work on the land from reproductive work in the kitchens.

Rama organizes monthly mutirões, each time in a different neighborhood. In the neighborhoods, the groups also hold their own mutirões. This collective work is another way for them to be together, support one another, and observe how each woman manages her backyard and fields. In the city, the consumer groups also participate in the mutirão to unload the foods that arrive every month.

Over time, Rama began reserving a percentage of the commercialization money in a fund that is used, among other things, to pay for the women’s transportation to the mutirões. It is not uncommon, however, for these funds to be needed to pay for medical exams or medications for one of the women or a family member. Or for a peasant that got into debt to cover for a treatment. Lack of access to healthcare is one of the problems they face — a symptom of the lack of access to public policies not only for agriculture but for fundamental rights.

When SOF began working in the Ribeira Valley in 2015, one of the first things the women farmers said was: “We know how to plant — we have done that our whole lives. We need to sell our produce.” As long as they have the guarantee of remaining on their lands, healthy foods produced agroecologically will remain in the countryside. And groups of people can organize to buy these foods. What is missing is expanding support for this production, which is inseparable from the lives of women, and improving logistics so that this food can reach people in the cities.